Under what circumstances can a foreign plaintiff sue for human rights violations that occurred abroad? The Alien Tort Claim Act (ATCA) gives federal courts in the United States jurisdiction over claims brought by foreign victims for torts committed in violation of international law or a US treaty. In recent years, alleged victims of international human rights abuses have invoked this statute to win judgments in US courts. However, not all of the cases succeed in meeting the high bar of the ATCA. Such was the case in Amergi v. Palestinian Authority which failed to meet the ATCA’s high bar. The suit arises from the murder of Ahuva Amergi, an Israeli citizen who was shot and killed as she drove her car in the Gaza Strip in February of 2002.

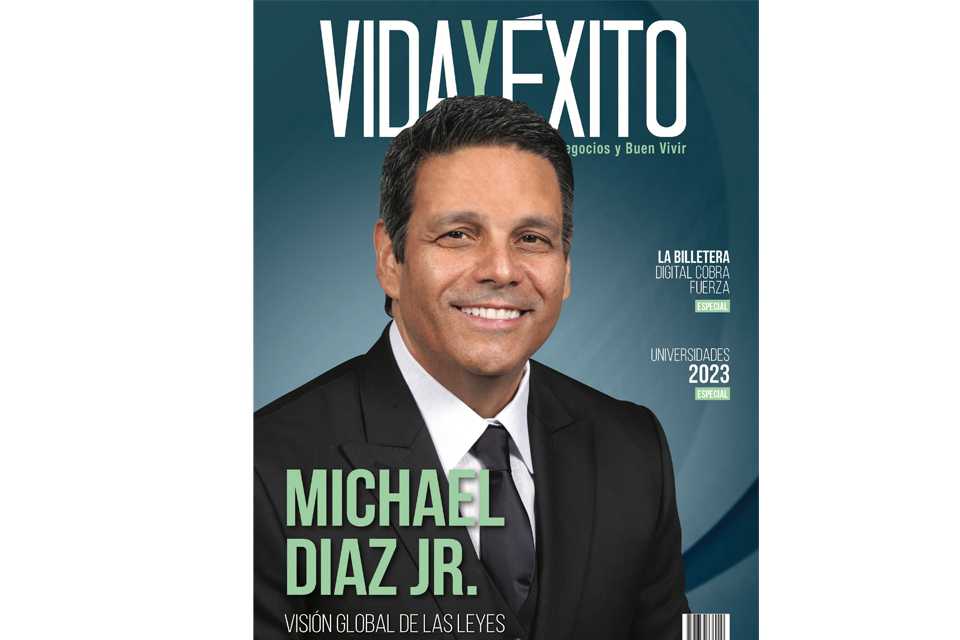

Will this decision make the U.S. courts begin to exercise considerable restraint in permitting claims under the ATCA? In this case summary, Michael Diaz, Jr. closely examines legal issues unique to ATCA cases against foreign governments, including establishing jurisdiction.

The U.S. Alien Tort Statute: Are U.S. Courts Open to the World?

The Alien Tort Claim Act (ATCA) gives federal courts in the United States jurisdiction over claims brought by foreign victims for torts committed in violation of international law or a U.S. treaty. As stability in many war-torn foreign countries deteriorates, ATCA litigation has steadily increased over the years. More and more human rights cases are now heard by U.S. courts for conduct committed in jurisdictions affected by civil war or civil unrest and where human rights protections are either inadequate or non-existent. However, the U.S. courts are permitted to recognize only a limited set of causes for international wrongs under the ATCA and not all of the cases succeed in meeting the high bar of ATCA. Such was the case in Estate of Ahuva Amergi v. Palestinian Authority.

The Facts:

The case was brought by individuals who claimed to be victims of human rights abuses committed by the Palestinian Authority in attacks on Israeli Citizens. The suit claims that Ahuva Amergi, an Israeli citizen, was shot and killed as she drove her car in the Gaza Strip in February of 2002, allegedly by agents of the Palestinian Authority.

The plaintiffs’ alleged, among other things, that the killing of Ahuva Amergi was an act of terrorism and violated the Geneva Conventions on the Law of War. The plaintiffs’ primary argument was that the killing of Ahuva Amergi by private actors in the course of an armed conflict is enough to give rise to subject matter jurisdiction under the ATCA.

The Decision:

The district court rejected the plaintiff’s claim on the ground that it did not have subject matter jurisdiction over the suit. The Eleventh Circuit agreed with the observations of the district court and further affirmed the dismissal of the action; finding that the act the plaintiffs alleged – a single killing by non-state actors purportedly in the course of an armed conflict – failed to meet the ATCA’s high bar.

In dismissing the case, the district court first explained that the complaint was pled primarily as a terrorism case. Since acts of terrorism were not cognizable under the ATCA, it thus had no subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to a terrorism theory. As to the second theory alleging violation of the Geneva Conventions on the Law of War, the district court determined that not every violation of the Geneva Conventions supports ATCA jurisdiction. The court relied on the principles enunciated in Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain in demonstrating whether a violation of the Geneva Conventions establish a breach of the laws of nations, a critical aspect to maintain jurisdiction under the ATCA.

In Sosa, the U.S. Supreme Court had determined that a single illegal detention of a Mexican national in Mexico by agents of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency for less than one day, custody of whom was then transferred to lawful authorities in the United States for prompt arraignment, did not violate any norm of customary international law so as to support a cognizable cause of action under the ATCA. The Sosa case arose from the kidnapping and murder of a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agent by members of a Mexican drug cartel. After an extensive investigation, the DEA concluded that Humberto Alvarez-Machain had participated in the murder. Although a federal district judge then promptly issued a warrant for Alvarez’s arrest, the DEA was unable to convince Mexican authorities to extradite him. Instead of continuing to pursue diplomatic options, the DEA hired several Mexican nationals to capture Alvarez and bring him back to the United States for trial. As so planned, a group of armed men proceeded to abduct Alvarez from his home, holding him overnight at a motel and bringing him by private plane to El Paso, Texas, where he was formally arrested by U.S. marshals.

After being acquitted of all charges against him, Alvarez sued Sosa, one of the Mexican nationals involved in his capture, under the ATCA for “a violation of the law of nations.” On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the lower courts’ decision to grant Alvarez relief under the ATCA. To determine which violations Congress originally had in mind when drafting the ATCA, the Supreme Court in Sosa looked to Blackstone’s Commentaries, which disclosed three relevant violations: “offenses against ambassadors, violations of safe conduct . . . and piracy.” Consequently, the Supreme Court held in Sosa that an ATCA plaintiff must show the specific violation of an enumerated norm of international law that, if left unaddressed, would “threaten . . . serious consequences in international affairs.”

The Sosa Court went on to dismiss Alvarez’s ATCA claim, finding that “whatever may be said for the broad principle Alvarez advances, in the present, imperfect world, it expresses an aspiration that exceeds any binding customary rule having the specificity we require.” In reaching this conclusion, however, Justice Souter disagreed with Justice Scalia’s narrower contention that federal courts should be precluded “from recognizing any further international norms as judicially actionable today, absent further congressional action.” Instead, Souter argued that “the judicial power should be exercised on the understanding that the door is still ajar subject to vigilant doorkeeping, and thus open to a narrow class of international norms today.”

Relying on the Supreme Court’s analysis in Sosa, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals found that Amergi’s murder, however horrific, does not implicate foreign relations concerns in the same way that would, for example, an assault on a foreign ambassador. In that ATCA cases would now require a high bar, the district court has maintained that to extend the ATCA to cover any violation of the Geneva Conventions would dramatically expand federal jurisdiction, in violation of the Supreme Court’s decision in Sosa. Against the legal backdrop of the Sosa case, the Eleventh Circuit noted that although federal courts are permitted to recognize a limited set of causes of action for international wrongs under the ATCA, their ability to do so is sharply circumscribed, both by precedent and by prudence.

The Eleventh Circuit explained that the ATCA Statute was initially passed at the beginning of the Republic in 1789, with only “minor amendments since that time,” which today provides federal jurisdiction over a limited class of international wrongs: “The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” Under this standard, The Eleventh Circuit further clarified that the federal subject matter jurisdiction exists for an ATCA claim when . . . three elements are satisfied: (1) an alien (2) sues for a tort (3) committed in violation of the law of nations.”

Furthermore, the Amergi case makes no claim of state action. The Eleventh Circuit observed that the Amergis’ complaint does not explain whether the conflict was a war, how long it had gone on, who was fighting, what they were fighting for, how the conflict had evolved, or how the tort at issue fit into the larger picture. The Eleventh Circuit further noted that the Amergis have neither asserted that there was any state action in the single act of alleged murder nor have they claimed torture, summary execution, multiple killing or any other distinct war crimes. Moreover, the Court noted that the Amergis did not make any sort of genocide argument, or any claim of ethnic cleansing, or any assertion that a group of Israeli Citizens, or Jews, had been targeted for removal or relocation. In conclusion, the Eleventh Circuit noted that the Amergis’ complaint failed to establish subject matter jurisdiction under the ATCA.

Implications of the Decision:

This important decision contributes to the growing body of ATCA and international case law, intertwined with politically sensitive matters of international concerns. The Amergi case would also have implications on the U.S. federal courts’ perspective on the struggle between Israelis and Palestinians, an issue of U.S. foreign policy that presents numerous diplomatic and political challenges for the White House today. The decision in the Amergis’ case, however, perpetuates a legal uncertainty that may make it difficult for plaintiffs to establish a foreign state’s liability for wrongful death under the ATCA and is bound to have important ramifications for private international law cases filed in U.S. federal courts.

![Especial abogados Salón de la Fama[61] 4](https://diazreus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Especial-abogados-Salon-de-la-Fama61-4-pdf.jpg)