When the Chinese legislature enacted a new criminal statute in 2009 penalizing unlawful acquisition and misappropriation of citizens’ private information, no one thought that the government would be serious in enforcing it. The reason was simple: privacy rights have not been fully defined in China, and unscrupulous exploitation of personal information, including sale and purchase of the same, is common practice. However, things started to change in June this year when the court in Beijing announced its judgment in the first criminal case involving infringement of private information. This enhanced privacy protection regime is likely to have far-reaching impact upon its overall business environment.

This article discusses the legislative updates, significant case developments and other important issues affecting the privacy sector in China.

When the Chinese legislature enacted a new criminal statute in 2009 penalizing the unlawful acquisition and misappropriation of citizens’ private information, no one thought that the government would be serious in enforcing it. The reason was simple: privacy rights have not been fully defined in China, and unscrupulous exploitation of personal information — including sale and purchase of the same — is common practice. For example, vehicle owners’ information is easily available in the market for about one cent per piece. By paying about USD 250, one can buy tens of thousands of pieces of vehicle owners’ information, including their names, cell phone numbers, home addresses, vehicle models, colors, etc. It was not surprising for someone who newly purchased a car to receive an unsolicited phone call a few days later trying to sell him/her a vehicle insurance policy.

Things started to change in June this year when the court in Beijing announced its judgment in the first criminal case involving infringement of private information. In that case, a former statistician at a Beijing airport shuttle company sold information about the company’s customers to two co-defendants, who in turn used the information to make fake shuttle passes. All three defendants got prison sentences. Then, in July, a similar case was tried in Whenzhou, Zhejiang Province. In that case a former police aide unlawfully accessed the National Traffic Administration Database and retrieved thousands of entries of vehicle owners’ information for sale at RMB 0.2 (2.5 cents in U.S. currency) per piece. The defendant likewise was sentenced to imprisonment. The largest and most controversial case, however, was tried in Shanghai. In that case, more than ten defendants purchased personal information on the internet or from information wholesalers, and then resold it for a higher price to businesses collecting individual information for marketing purposes. Most of the defendants were sentenced to prison terms ranging from three months to two years.

All the three cases were based on the same criminal statute enacted in 2009, which reads:

Any employee of state agencies, or financial, telecommunication, transportation, medical, and similar institutions who sells or unlawfully provides to others individual private information he/she obtains in the course of conducting official business or rendition of services in violation of the state’s laws or regulations, the offender shall be subjected to imprisonment of less than three years, or short-term confinement, and/or criminal fines, provided that the circumstances of the offense are serious.

Any person who steals individual private information described in the preceding paragraph, or obtains such information in unlawful means shall be subjected to the same penalties prescribed above, if the circumstances of the offense are serious.

If the offender is an entity, the offending entity shall be subjected to criminal fines, while its direct supervising personnel or any other personnel directly responsible for the commission of the offense shall be penalized by the same measures applicable to individual offenders.

China Penal Code (the seventh amended version of 2009), Art. 253(1)

Article 253(1) is not crystal clear as to what behavior it prohibits. For example, the statute is unclear as to under what circumstances an individual who is not an employee of any state agency or public institution can be held liable for illegally obtaining personal information. Read in its context, the provision “[a]ny person who steals individual private information described in the preceding paragraph . . . if the circumstances of the offense are serious” can be interpreted to mean: (1) a defendant will be liable for stealing or unlawfully obtaining personal information that has been unlawfully acquired and/or disclosed by an employee of a government agency or public service company of institution in the course of transacting official business; or (2) a defendant will be liable for unlawfully obtaining personal information as long as he/she steals or otherwise employs unlawful means in obtaining the same, no matter whether such information was from an employee of a government agency or public service company or institution. Which interpretation controls depends on what the phrase “such information” in the second paragraph refers to. While the cases in Beijing and Wenzhou are consistent with the first interpretation, the court in Shanghai seems to adopt the second interpretation. Indeed, the prosecutor in the Shanghai case did not provide evidence that any government or public institution employee was involved in unlawfully releasing the subject information which the defendants purchased and sold.

A more serious problem is the lack of clear of definition of “unlawful means” for obtaining personal information. For example, in the Shanghai case, most of the defendants were found guilty for merely purchasing and reselling personal information. Why is purchase of personal information punishable under Article 253 when the information has already been released into the public realm? Although the court implied that in this particular case the defendants should have known that the information they purchased were unlawfully obtained based on the nature of the information (individual ID numbers, vehicle registration information, etc., e.g., information not ordinarily available from open sources) and the defendants’ familiarity with the practice of information wholesale, it did not clarify what constituted illegal acquisition, and under what circumstances was purchase of personal information unlawful.

It is likely that the new Private Information Protection Act, which is in the legislative pipeline and due to be released soon, will provide clearer guidance. Designed to better define citizens’ rights in privacy of information and to provide better protective measures, the statute will be more specific than any existing law on the subject and will create private causes of action for unlawful exploitation of personal information.

China’s enhanced personal information protection regime will have significant impacts on businesses operating in China, domestic and international alike. For those companies that resort to individualized marketing campaigns to promote their products or services (for example, personal assets management companies), it is time to revise their marketing strategies to ensure that information regarding potential clients are lawfully obtained. Companies also need to be more careful when selling, sharing, and disclosing their customers’ information. The financial sector is probably more affected than other businesses. Many are concerned that enhancement of personal information protection will hamper the fledging credit rating and reporting system, which is much needed in a maturing financial service market but which relies heavily on the agency’s ability to collect, share, and disclose information.

For litigator(s), an enhanced private information protection system will create more obstacles to collection of evidence for use in litigations. Because discovery mechanism is almost non-existent in the Chinese court system, currently litigants and their attorneys have to resort to private investigative measures, including employment of private investigators and personal contacts (guanxi) at government agencies, to obtain information about opposing parties and key witnesses, and to collect evidence. With the more rigorous privacy protection regime in place, litigation and arbitration in China will be more difficult. Because China’s enhanced privacy protection regime has far-reaching impact upon its overall business investment, foreign companies operating in China, like domestic businesses, pay close attention to the development of privacy law in China. For example, just recently the Legal Committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai held a well-attended seminar focusing on China’s developing privacy law and its impact on international businesses. Although enhanced protection of privacy rights is indeed a good thing from the perspective of civil rights, its pros and cons as to the business environment are not yet evident.

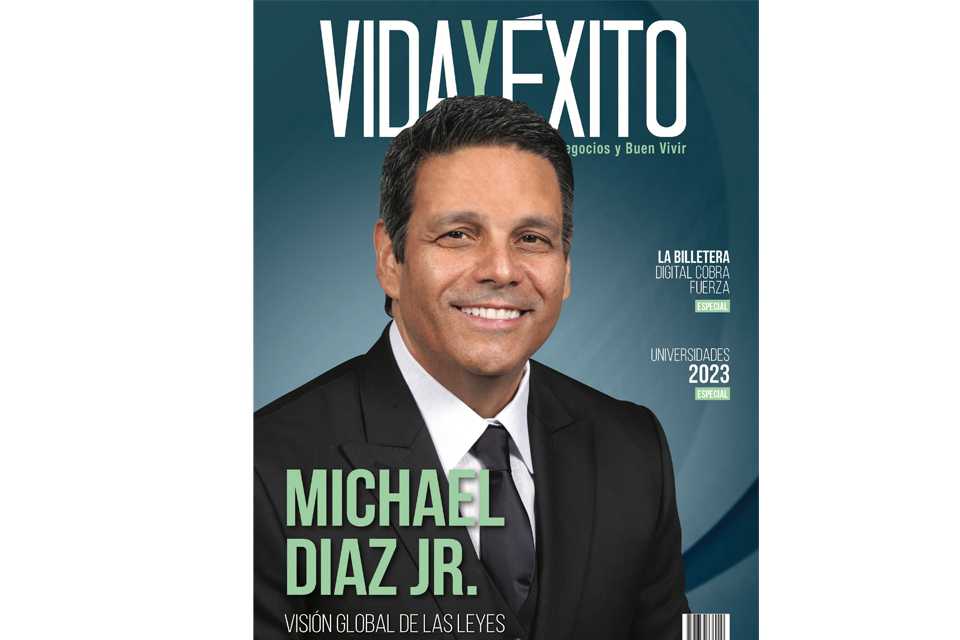

Please contact Michael Diaz, Jr. with further questions. Thank you.

![Especial abogados Salón de la Fama[61] 4](https://diazreus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Especial-abogados-Salon-de-la-Fama61-4-1-pdf.jpg)