By Jeff Ernst

When Yani Rosenthal – a former legislator who served nearly three years in a U.S federal prison for money laundering connected to drug trafficking – arrived home to Honduras in August, he got a hero’s welcome.

A crowd of reporters rushed forwards with cameras and microphones, and a caravan of fans shouted, cried and waved red flags emblazoned with his name in white.

Rosenthal – the scion of what was once one of the most rich and powerful families in the country – is now preparing to launch a bid for the presidency as Honduras kicks off its campaign season ahead of a crucial 2021 election. The move is raising eyebrows both at home and abroad.

“I think for the gringos, it’s inconceivable that there are people in Honduras thinking I might be the candidate [for president],” said Rosenthal, in aninterview with a local television station.

But in a country where the current president, Juan Orlando Hernández, faces serious allegations of drug trafficking himself, the idea that Rosenthal could pull off such a feat isn’t that far-fetched.

“People here have lived with the phenomenon of drug trafficking,” said Edmundo Orellana, a former attorney general who supported Rosenthal in the past. “They have complied with, coexisted with and even benefitted from the drug kingpins, who were widely known, respected and sought after by society.”

At its peak, roughly a third of the cocaine consumed in the U.S. – a market valued in the tens of billions of dollars – transited through Honduras, one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere.

“It sustained the economy,” said Orellana. “Everyone knew it.” In particular, it made the rich like Rosenthal richer. It also made Honduras one of the most dangerous countries in the world and forced countless numbers of its citizens to migrate north.

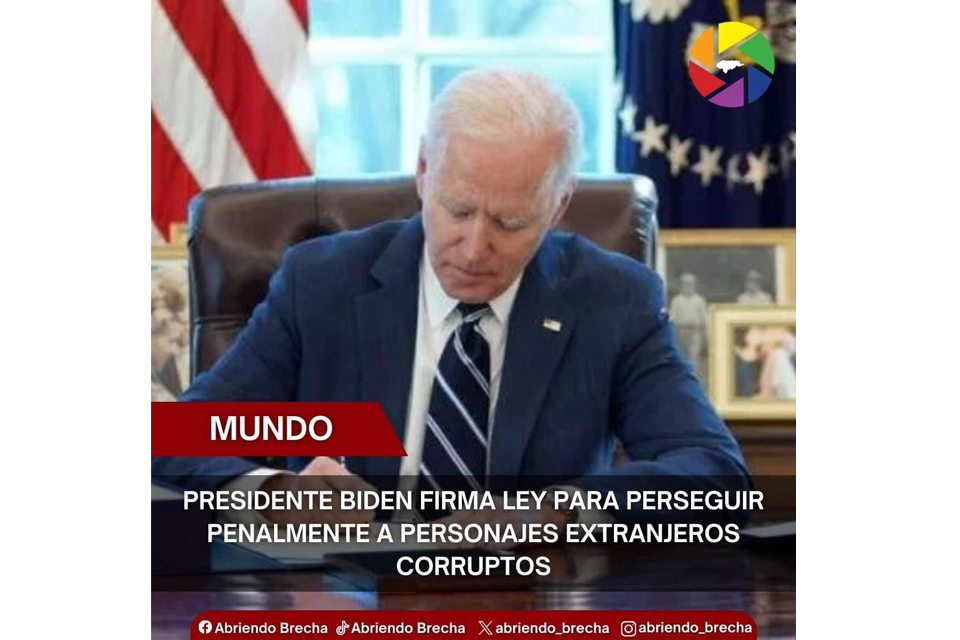

In 2015, the U.S. Treasury Department announced sanctions against Rosenthal, his father, a cousin and their vast business empire. At the time, the Rosenthal family owned a bank, soccer club, newspaper and meatpacking plant while acting as kingmakers in the government.

“They were untouchable in Honduras until the accusations by the United States,” said Ismael Zepeda, an economist at the Honduran thinktank FOSDEH.

Some of their businesses were used to launder money for multiple drug trafficking organizations, including the infamous Cachiros, according to U.S. authorities. Following the sanctions, Honduran authorities moved to quickly seize much of the Rosenthal’s empire, which is now the subject of a high-stakes, billion-dollar lawsuit filed by the family against the government to recuperate its assets. Should they win, the government could end up owing the Rosenthals the equivalent of nearly ten percent of its annual budget.

“It would be paid at the cost of reductions in healthcare, infrastructure, salaries and more,” said Zepeda.

The Cachiros, led by brothers Javier and Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga, were cattle runners turned drug smugglers who operated along the north coast of Honduras. They were sanctioned by the U.S Treasury in 2013, leading them to become informants for the U.S’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Two years later, the Cachiros turned themselves in, bringing with them secretly taped recordings and confessing to a slew of crimes, including a role in at least 78 murders.

According to Rosenthal, the Cachiros became a client of his family’s meatpacking plant in the early 90s. But it wasn’t until 2008, after he had left a cabinet post in government, that he found out they were drug traffickers, he claimed.

“I should have cut him off then,” said Rosenthal. “I allowed him to continue selling cattle to the meatpacker for five more years.”

But the secret had been out since at least 2003 when the Cachiros staged a violent takeover of what was then known as the Atlantic Cartel. The cattle, according to prosecutors and their star witnesses, the Cachiros, were purchased with drug proceeds in order to launder money.

“When he was sanctioned by [the treasury], I found out and immediately cut him off as a client,” said Rosenthal.

![Especial abogados Salón de la Fama[61] 4](https://diazreus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Especial-abogados-Salon-de-la-Fama61-4-pdf.jpg)